Copyright © 2010 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 56, No.3 - Fall 2010

Editor of this issue: M. G. Slavėnas

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2010 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 56, No.3 - Fall 2010 Editor of this issue: M. G. Slavėnas |

Book review:

Antanas Andrijauskas. Litvak

Art in the Context of the École de

Paris, Vilnius: Library of Vilnius Auction, 2008. ISBN

978-609-

8014-01-3.

Paris assumed the leadership of the modern art world during the twilight years of the Belle Époque, and then virtually monopolized the role until World War II. In the course of that halfcentury, hundreds of artists flocked to the art capital, convinced that they simply had to live, work, and exhibit in the City of Light. Otherwise they would always be conscious of an inferiority, either for not having studied under one of the academic masters associated with the École des Beaux-Arts or, more important to some, for not having personally come to terms with the innovations that followed on the heels of Impressionism. And there were so many of these new movements: Symbolism, Cloisonnism, the Nabis, Synthetism, Fauvism, Cubism, Orphism, Purism, and Surrealism, to name the most prominent ones taking turns in the limelight.

The École de Paris became the catchall umbrella term for those painters and sculptors who either stood clearly apart or could not be comfortably accommodated within one of these newly minted and mostly French modern art movements. Coined in 1925 by André Warnod, this indiscriminate, supersized label quickly and haphazardly took on a life of its own, referring to just about any foreign artists or aspiring amateurs in Paris, however tenuous or vague their associations with the city’s cosmopolitan art scene. Drawn from every corner of the globe, this population of accomplished artists, art students, and part-time enthusiasts numbered in the thousands. Among them, Nadine Nieszawer recognized 151 Jewish artists in the study Peintres juifs à Paris, École de Paris 1905-1939. Many were from Eastern Europe, the Litvak subset comprising a large and distinct contingent, notable for producing Marc Chagall, Jacques Lipchitz, Chaim Soutine, Ossip Zadkine, and other figures. They, together with some of their less well-known colleagues, are the subjects of the study at hand – Litvak Art in the Context of the École de Paris by Antanas Andrijauskas. A few remarks should help us to appreciate this work.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the recently developed Montparnasse section on the Left Bank had turned into the artists’ neighborhood of choice, overtaking and surpassing their earlier preference for the seedy Right Bank and its picturesque Montmarte. The new area’s relative proximity to the École des Beaux-Arts aided the transition. The bars, brasseries, cabarets, hotels, and studios near the Carrefour Vavin Boulevard intersection – especially the cafés La Rotonde, Le Dome, La Select, La Coupole, Café du Parnasse, and Cremerie Leduc – became action central for Montparnasse painters and poets, writers and critics. Scandinavians initially preferred the Café de Versailles, later switching their allegiance to Le Dome. The German contingent also congregated there, but the outbreak of World War I changed matters overnight. Americans liked to dine out at Le Studio Hotel, buy their grapefruits at Hazard’s, and play billiards or nonstop poker in the back rooms of Le Dome. The Wall Street crash of 1929 brought most of them home. Poles and Russians customarily patronized Café de la Rotonde, where, according to a local wit, “all the dialects on earth were spoken, sometimes even French.”

Artists freshly in Paris sought out the establishments where their native tongue could be heard, home-language newspapers were available, and old acquaintances encountered. Thus, Jewish artists from Germany, Austria, Poland, Russia, and Eastern Europe in general headed for Le Dome. Alternatively, they could also be seen at the Café de la Rotonde, a regular hangout for Picasso, Apollinaire, Fernand Léger, De Chirico, Diego Riviera, Leon Bakst, Trotsky, and some say Lenin. Professional interests as well as linguistic and ideological differences may have kept the frequenteurs apart at their respective tables. The artists, however, could always mix and meet as they pleased on the neutral, common ground of museums, galleries, ateliers, and studios.

Uppermost on the new arrivals’ agenda was the matter of lodgings, which many found in La Ruche, an international artists’ colony of several buildings located just south of the Montparnasse district. (The area’s central landmark structure resembled a beehive – la ruche in French.) Its idealistic landlord charged barely enough rent for the studios and rooms to break even, making it a haven for indigent newcomers. Apollinaire, Léger, Modigliani, Archipenko, and Brancusi had lived there before moving on and achieving renown. Such figures apart, its largest group consisted of poor Jewish artists recently arrived from Eastern Europe, Poland, and Russia. At one time or another, Marc Chagall, Jacques Lipchitz, Chaim Soutine, Ossip Zadkine, Jules Pacsin, Elie Nadelman, and Oscar Miestchaninoff had quarters there. So did Chana Orloff, Pinchus Kremegne, Isaac Dobrinsky, Moishe Kogan, Leon Indenbaum, and a host of other, even less well-known Litvak artists. A hothouse of inspiration and cross-fertilization, La Ruche could jump-start a talented person’s creativity as effectively as the Montparnasse café scene.

Since many Jewish artists had arrived in Paris as teenagers or just in their twenties, the paper trail of their artistic careers could begin with a studio rental at a place like La Ruche, enrollment in an atelier, and so on. Of course, those who had finished their studies in Germany or Austria, had established links with a local artist group, and had exhibited in a gallery or two, came to Paris with a traceable track record. By contrast, and until quite recently, the paper trail of Litvak artists who had arrived from the now defunct Soviet cultural space stopped at the old Iron Curtain, no matter whether young or mature and accomplished. Arthur A. Cohen put it this way in The Circle of Montparnasse – Jewish Artists in Paris 1905-1945: “With the exception of Marc Chagall’s fanciful memoir of his youth in the small city of Vitebsk, we have little or insufficient information about the childhood, youth, or education of the Jewish artists of Eastern Europe who became the Jewish painters and sculptors of Montparnasse.”

Antanas Andrijauskas’s study begins to supply exactly the sort of information that was lacking in 1985 when the above words were penned. He clarifies that the so-called “Jewish artists of Eastern Europe” were mostly Litvak painters and sculptors originating in the Jewish Pale of Settlement, the lands where, by imperial edict, the Jews of the Russian Empire were required to live. The chapter entitled “The Uniqueness of Litvak Culture,” explains that the Pale was an immense area, covering present-day Latvia, Lithuania, Belarus, and the Ukraine, plus parts of eastern Poland and western Russia. Stretching from the Baltic to the Black Sea, it stopped at the eastern borders of Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Historically, the Pale’s territory closely approximated the lands of the Polish- Lithuanian Commonwealth, which Catherine II annexed to the Russian Empire at the end of the eighteenth century. In 1791, about 1.5 million Jews lived in the Pale; by 1917 their numbers had grown to about 7 million. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania’s cultural space was called Lite in Yiddish, Lita in Hebrew. Virtually every Jew in the Pale spoke Yiddish; the millions speaking the Lithuanian dialect of Yiddish were called Litvaks.

England expelled its Jews in 1290, France in 1394, and Spain in 1492. They started arriving in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from the fourteenth century onwards and established deep roots in the fabric of that tolerant realm. Obtaining various economic and commercial privileges, Jews lived in relative peace and were generally much better off than their kinsmen living elsewhere in Europe. The favorable conditions helped them maintain their religious traditions, develop selfawareness, and create a distinctive cultural identity. This goes a long way to explain why Litvak descendants, even several generations removed, often refer to their identity in terms of Lita. Cities like Brest-Litovsk, Minsk, Vitebsk, Kiev, and Lvov (Polish Lwów) had sizable Jewish communities, but Vilnius (Vilno; Polish Wilno) stood out as a preeminent and distinguished cultural center. Renowned since the late eighteenth century among Jews for its learning and scholarship, it hosted important publishing houses, the remarkable Strashun Library, plus other important collections of rabbinical texts and manuscripts. Nicknamed the “Jerusalem of the North,” by 1900 the city had more than a hundred synagogues and ten yeshivas led by rabbis of the highest rank. There was a saying in Yiddish: “To earn a living, go to Łódź, Warsaw, or Odessa, but to gain wisdom, go to Vilnius.”

The old capital of Lithuania also attracted Jewish youths seeking an art education. The Vilnius School of Drawing, unlike its discriminatory counterparts in the Russian Empire, accepted Jewish students, placing them side by side with local bluebloods and Roman Catholics. Jews could also enroll in the Jozef Montwill Trade School for Drawing and Painting, founded in 1893, and the Mark Antokolsky School of Industrial Art, founded in 1905. Outside Vilnius, Jewish youths were also accepted by the Kaunas School of Art and, further afield in Vitebsk, into Yehuda Pen’s School of Painting and Drawing. The Litvak artists settling down in Paris had for the most part been trained at one of these institutions.

Tsarist Russia made life very hard for its Jewish subjects and, eventually, two million of them left the Pale. Their eagerness to leave can be suggested by a few examples. For instance, starting in the 1840s, Jewish boys as young as twelve were sent to military schools. Reaching eighteen, they were drafted into the army to serve for the next twenty-five years. Harassment by the Russian rank and file could be avoided if they converted to Christianity. Czar Alexander II repealed these measures, but his assassination in 1881, in which a Litvak woman was implicated, fostered anti-Semitism and led to several pogroms. The next tsar decided to force a third of the Jews in the empire to become Orthodox Christians, another third to emigrate, and the remainder to assimilate or somehow disappear. The Japanese destruction of the Russian imperial fleet in 1905 was blamed on various “Jewish plots,” resulting in another wave of pogroms. And in 1915, in an early case of ethnic displacement, the Litvak communities closest to the war front with Germany, accused by the Russians of collaborating with the Germans, were uprooted en-masse, tens of thousands finding themselves deported to the Urals, Siberia, or deposited in some other godforsaken corner of the Russian Empire. It is little wonder that those that could leave tsarist Russia left, most of them heading for the United States.

On the way, many Litvak artists stopped for a while or permanently settled down in Paris. In the chapter “The Litvak Expansion to Paris,” Andrijauskas discusses the Montparnasse art scene and the important role played by the patronage of Leopold Zborowski; he addresses the search for a Jewish national art, and questions the existence of a specifically Jewish art. Having sketched out the larger picture, he then devotes the book’s remaining two hundred pages to particular artists, parsing the material into seven chapters. Chaim Soutine, Marc Chagall, Lasar Segall, Max Band, and Arbit Blatas receive one chapter apiece. The sculptors Jacques Lipchitz, Ossip Zadkine, and Leon Indenbaum are treated together in one chapter, and the painters Michel Kikoine and Pinchus Kremegne in another.

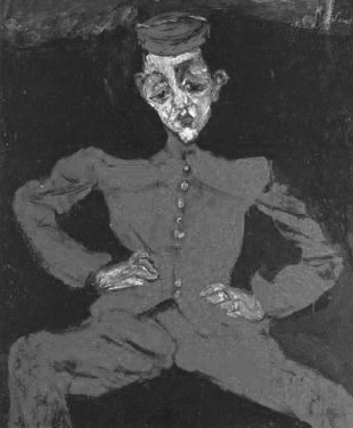

The chapters on individual artists are unequal in length. Chaim Soutine receives the most attention, some seventy pages, three times more than Chagall, the next closest artist, and six times more than the dozen text pages allotted to Blatas, the artist with the shortest chapter. Andrijauskas’s esteem for Soutine, which led to the disproportionate coverage, is explained at the very outset: “As I delved deeper into his legacy and that of other twentieth-century painters, I came to the conclusion that Soutine stands tall alongside Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Georges Rouault, and Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis.” Like Čiurlionis before him, Soutine also “created a world of images filled with subtle lyricism and an almost mystical sense of mystery, (and) can be assigned to the very rare category of the most authentic painters.”

Unlike the initial historical overview, written from a detached observer’s point of view, the chapters devoted to individual artists convey Andrijauskas’s enthusiasm for their artworks at just about every opportunity. For the prevailing tone, consider the quotes just cited. Praise abounds, while critiques are hard to find. There is no doubt that Andrijauskas has studied the Litvak artists at length and in depth. Intriguing leads and insights peppering the text demonstrate his thorough command of the subject. However, his enthusiastic admiration sometimes mars the scholarship, often shortchanging or entirely evading longer explanations.

A closer look at the treatment of Soutine, which corresponds to discussions of other artists, should suffice to convey our reaction to the work in its entirety. We read that Soutine had much in common with his fellow Litvak artists. He had studied in Vilnius, lived at La Ruche, frequented the cafés most popular with his compatriots, spent many hours at the Louvre, was inspired by the usual list of old masters and contemporary painters. This is par for the course. But when it comes to particulars, all too often they remain elusive.

For instance, we read that “negative childhood experiences” affected Soutine’s sensibilities, but are not informed whether it was a matter of parental abuse, abject poverty, mockery by classmates, humiliation by teachers, something else, or a little of all of the above. Or, perhaps, the author was too squeamish to provide details? Whatever the case, in this matter the reader is left in the dark. Andrijauskas further writes: “In many of the texts about Soutine’s life and works we encounter not a few mystifications, inaccuracies, and tendentious, contradictory claims intended to prettify this ill-fated artist with the sort of exotic new details that are fascinating to philistines.” Given the damning indictment it is entirely reasonable to expect Andrijauskas to then identify the perpetrators, counter their false claims, reveal the truth, and persuade the reader. Once again, what little there is of a follow-up remains weak; the statement is not clarified, and the reader remains skeptical and/or mystified, guessing the identities of the “philistines” and surmising their “misrepresentations.”

The discussion of the art is often just as vague. Phrases like an “authentic artist,” “true genius,” “universal personality,” “exalted canvases,” and “tragic modernism” fail to convince for lack of evidence and backup information. It is also of little help to say that Soutine was greatly interested in Fouquet, Rembrandt, Tintoretto, El Greco, Velazquez, Goya, Ingres, Corot, Courbet, Chardin, van Gogh, Cézanne, Bonnard, Picasso, Matisse, Rouault, Jawlensky, Valoton, and Utrillo. These artists differ vastly among themselves and, presumably, each one interested Soutine for different reasons. Each alleged influence requires clarification; otherwise, such listings become little more than namedropping. Admittedly, Soutine’s color use and preferences are occasionally addressed and compared, but those passages are short and far between. The issues of Soutine’s compositional strategies and brushwork were also sidestepped. Jules Pacsin used to comment that every ghetto had artists aplenty painting like Soutine. Then there were Adolphe Basler’s observations. He was a Jewish art critic writing in Paris at the time, who termed Soutine’s brushwork Schmiermalerei, that is, smeary and greasy spreads of thick and loose impasto. One way or another, such less than complimentary views have to be directly confronted and dealt with. Likewise for Soutine’s links to expressionist painters, where further discussion and comparative analyses would have been extremely helpful.

Regardless of these reservations, it must nonetheless be praised for illuminating the artistic topography of “Eastern Europe,” a region filled with countries, cities, and shtetls, all of them having proper names and their unique histories. The region is not the undifferentiated, generic terra incognita so commonly encountered in Western publications. Historians and art lovers interested in the Litvak artists and their creative work will welcome Andrijauskas’s book. The milieu that produced the Litvak artists has become less of a mystery, less obscure. He has unearthed many long-forgotten nuggets of information about these artists, also rescuing from anonymity and obscurity the teachers and the art schools who inspired and trained so many of them. The literature about Litvak artists is much more plentiful in French, so it was a smart decision to issue this work in English, enabling a much a larger audience to better appreciate their place in the Paris art scene.

K. Paul Žygas

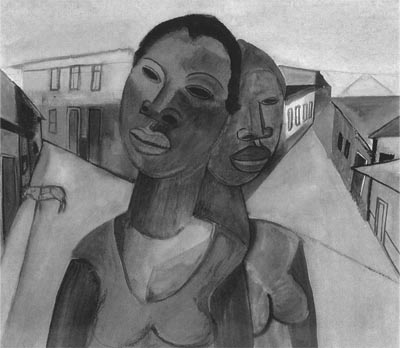

L. Segall, "Young Black

Women in a Small Village", 1929.

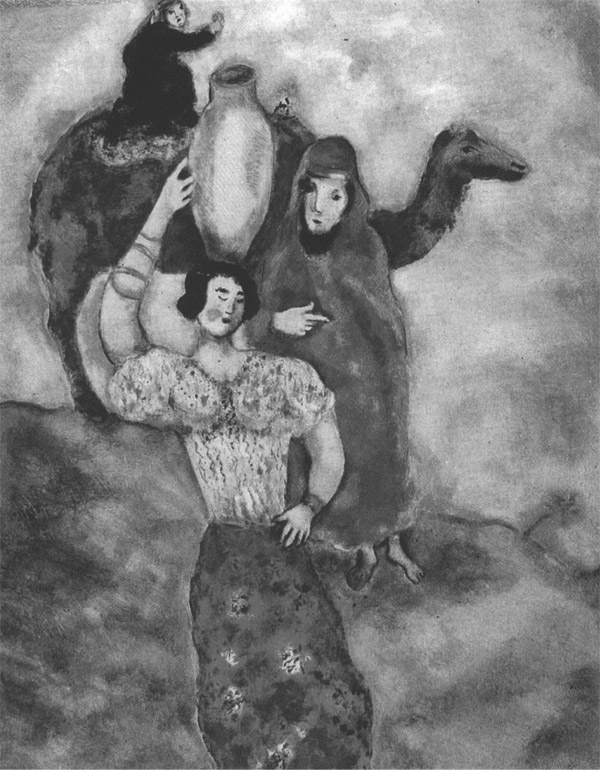

M. Chagall, "Rebecca", 1931.

C. Soutine, "Bellhop at Maxim’s", 1933.

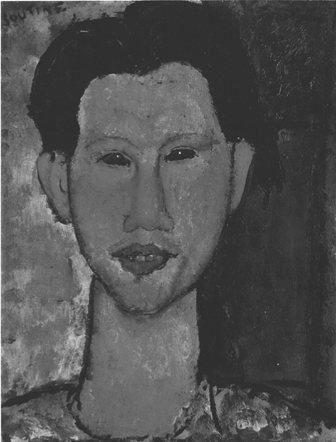

A. Modigliani, "Portrait of C. Soutine", 1916.

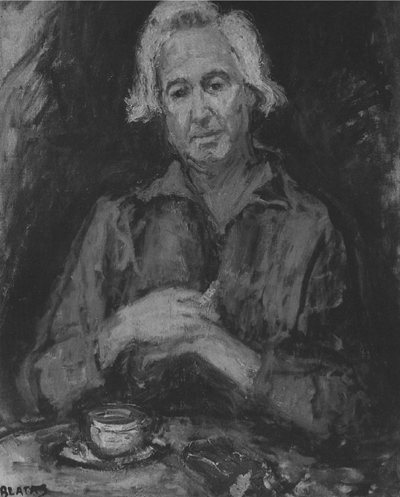

N. Blatas, "Mané-Katz", 1948.